In our previous article, we explored how the combination of ultrasound-guided modified Seldinger technique and arterial catheterization can help overcome the challenges of arterial access in critically ill patients. However, for this commonly performed clinical procedure, are there still fundamental concepts and techniques that we should reinforce and review?

Today, let us take a closer look at a 2023 article published in the Emergency Medicine Australasia titled “Arterial Catheterization.”

The article raises several key questions, which we have summarized and interpreted as follows:

Summary of Key Questions:

.png)

I. Indications

Primary: Continuous blood pressure monitoring (e.g., patients in shock requiring vasoactive agents, aortic dissection, or when non-invasive blood pressure monitoring is unreliable).

Secondary: Frequent arterial blood sampling.

II. Selection of Puncture Site

Preferred site: Radial artery (easy access, good collateral circulation, and low complication rate).

Other possible sites: Femoral artery, ulnar artery, brachial artery, dorsalis pedis artery, axillary artery, and posterior tibial artery.

Characteristics of each site:

Femoral artery: Lower catheter failure rate (~5%) compared to radial artery (~30%), and infection risk is not necessarily higher.

Ulnar artery: More tortuous course.

Brachial artery: Lacks collateral circulation; major complication rate around 0.35%, higher than that of radial artery (0.03%).

Distal radial artery: Technically more challenging but not inferior to the traditional radial access.

III. Contraindications and Complications

Contraindications: Proximal traumatic arterial injury, local infection at the puncture site, inadequate collateral circulation, and coagulopathy.

Complications:

Serious complications (rare): Ischemia causing permanent damage (<0.1%), local infection (<1%).

Common complications: Pain, paresthesia, bleeding, transient radial artery spasm (<50%), hematoma (15–50%).

IV. Procedure

1. Equipment preparation:

Necessary supplies (rolled towel, tape)

Infection prevention materials (antiseptic solution, sterile drapes, etc.)

Local anesthetics (1–2% lidocaine)

Arterial catheterization kits

Materials for fixation

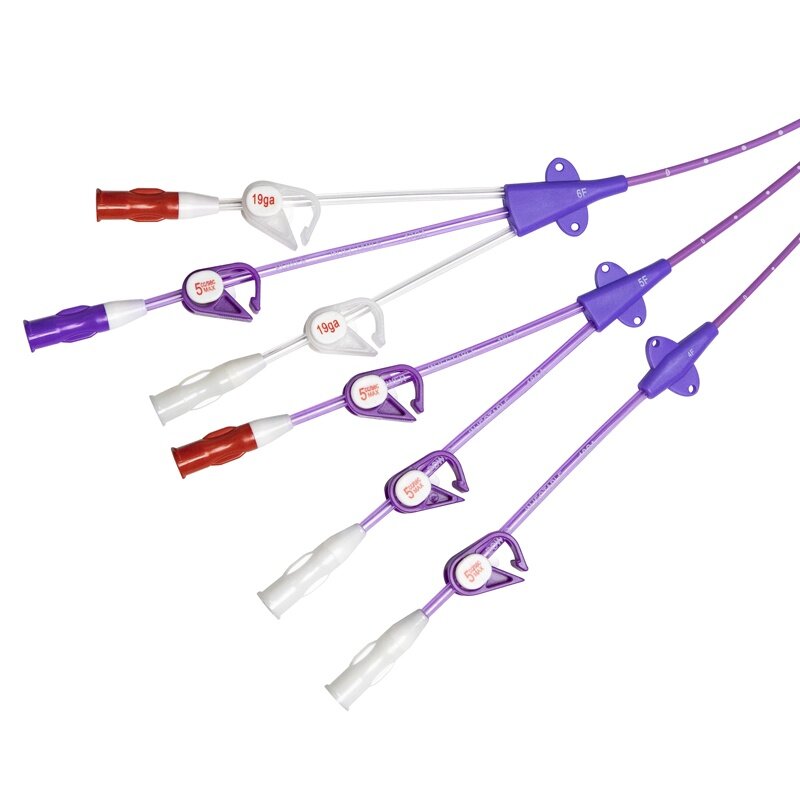

2. Types of catheterization kits:

a. Traditional Seldinger technique (higher first-attempt success rate)

.png)

b. Integrated Modified Seldinger Technique (allows faster catheter placement, but if the attempt fails, the entire kit must be discarded)

.png)

c. 20G Peripheral IV Catheter (not recommended for routine use)

.png)

3. Patient Positioning (Radial Arterial Cannulation):

A wrist extension angle of approximately 45° is recommended. Extension beyond 60° may reduce the success rate.

.png)

4. Adjunct Techniques:

Ultrasound guidance is recommended as the first-line approach in difficult cases. Real-time ultrasound guidance is superior to skin marking alone.

5. Local Anesthesia:

For awake patients, administer 1–2 mL of 1% lidocaine. There is no evidence indicating that lidocaine induces vasospasm or obscures the artery.

6. Pharmacologic Preparation:

There is no conclusive evidence supporting the use of systemic medications prior to cannulation to improve radial artery palpation.

7. Securing the Catheter:

There is no optimal method supported by strong evidence; institutional practice should be followed. Routine suturing is not recommended.

8. Sterile Technique:

At minimum, sterile gloves, a sterile drape, and a skin antiseptic should be used. Full barrier precautions are required for central sites.

V. Post-Procedure Considerations

1. Interpretation of Arterial Waveforms and Troubleshooting:

Ensure the transducer is properly leveled at the phlebostatic axis, corresponding to the level of the heart—approximately 5 cm below the sternum in a supine patient. Any unintentional change in transducer height may result in underestimation or overestimation of arterial pressure.

Underdamping will artificially elevate systolic pressure, depress diastolic pressure, and produce a narrow, sharply peaked waveform with a prominent dicrotic notch. Common causes include stiff tubing or transducer malfunction. This can be mitigated by using short, stiff tubing, minimizing stopcocks, avoiding modifications to prepackaged kits, or using commercially designed damping-optimized systems.

Overdamping is common and leads to underestimated systolic pressure, overestimated diastolic pressure, reduced pulse pressure, blunting of the waveform upstroke, and loss of the dicrotic notch. Causes may include a deflated pressure bag, air bubbles, thrombus formation, kinks in the tubing or catheter, or loose connections.

Troubleshooting steps include adjusting wrist position, ensuring catheter patency, checking tubing and all connections, flushing the catheter to clear thrombi or air bubbles, and considering replacement of the tubing and/or catheter.

A fast-flush or square wave test can help differentiate overdamping from underdamping by observing the oscillation pattern following a brief saline flush.

.png)

2. Catheter Removal Timing:

Recent evidence suggests that routine catheter replacement is not recommended. Removal should be performed when at least one clinical indication related to CRBSI (e.g., high fever) occurs or when the catheter is no longer required for therapy.

3. Post-Removal Care:

Apply direct pressure for 10 minutes (longer for femoral access or anticoagulated patients).

Inspect the catheter to ensure it is intact.

Monitor the affected limb’s neurovascular status for at least 15 minutes.

VI. Special Considerations in Pediatrics

1. Catheter Size:

<10 kg: 22–24G

10–40 kg: 22G

> 40 kg: adult-sized catheter

2.Puncture Sites:

Additional options include the temporal artery and umbilical artery.

3. Adjunct Techniques:

Ultrasound guidance is recommended to improve first-attempt success rates, and guidewires may be used as needed.

4. Complications:

Overall complication rates are low (~0.2%), but femoral artery complications are more common in infants and neonates.

VII. Key Conclusions

Serious complications are rare.

There is no evidence that arterial catheterization improves mortality or morbidity.

The Allen test is not recommended for predicting collateral circulation or complication risk.

Heparinized saline in the transducer bag does not prevent thrombus formation.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)