Reference Source: Indications for peripheral, midline and central catheters: summary of the MAGIC recommendations, Nancy Moureau and Vineet Chopra

Patients admitted to acute care frequently require intravenous access to effectively deliver medications and prescribed treatment. For patients with difficult intravenous access, those requiring multiple attempts, those who are obese, or have diabetes or other chronic conditions, determining the vascular access device (VAD) with the lowest risk that best meets the needs of the treatment plan can be confusing. Selection of a VAD should be based on specific indications for that device. In the clinical setting, requests for central venous access devices are frequently precipitated simply by failure

to establish peripheral access. Selection of the most appropriate VAD is necessary to avoid the potentially serious complications of infection and/or thrombosis. An international panel of experts convened to establish a guide for indications and appropriate usage for VADs. This publication summarises the work and recommendations of the panel for the Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC).

Method

Recognising the need to establish evidence-based indications for intravascular devices and specifically PICCs, an international group of expert physicians, clinicians and one patient was selected to work together as part of a University of Michigan/Society of Hospital Medicine-funded initiative. In this initiative, the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method (Fitch et al, 2001) was applied to develop criteria for the selection of the best VAD for each patient. A systematic literature review was performed and disseminated to the 15-member panel for evaluation with the 665 patient scenarios. To determine the effect on clinical decision-making, devices including peripheral intravenous catheters, ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous catheters, midline catheters, non-tunnelled central venous catheters (CVCs), tunnelled CVCs, and ports, were compared with PICCs. Additionally, scenarios evaluating the appropriateness ofindividual devices were also created. Each scenario was rated based on appropriateness of PICC or other VAD usage. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method incorporated information synthesis, panelist selection, patient scenarios, a rating process and analysis of results all specific to VADs.

Results

The results of the review by the Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC) panel included ratings from 391 unique indications of appropriateness or inappropriateness for PICCs and other VADs with two rounds of in-person rating scenarios by the panel (Chopra et al, 2015a). The final results established 38% of these indications as appropriate, 43% as inappropriate and 19% neutral or uncertain for the 665 scenarios. Details for each device are summarised in the following sections.

Peripheral access (PIV, USGPIV)

Peripheral catheters establish access into the veins and arteries of the arms and, less frequently, legs or other paediatric or neonatal applications of the scalp (Rickard et al, 2012; McCay, 2014). They are inserted using a direct visual approach or with visualisation devices such as infra-red or ultrasound technology. Peripheral access is considered less invasive than central access and has a lower risk of infection (0.5/1000 catheter days) (Maki et al, 2006; Hadaway, 2012). Peripheral catheters are considered appropriate for treatment of peripherally compatible medications and solutions (less than 900 mOsm/litre, not vesicant or irritant) when the duration of treatment is 6 days or less (Table 1) with transition to midline or PICC when duration is extended (Periard et al, 2008; Gorski et al, 2016). When multiple peripheral catheter attempts fail, the designation of difficult intravenous access (DIVA) may lead to assessment and access with ultrasound or other forms of visualisation technology (Figure 1). Success is enhanced with deeper ultrasound-guided access and the use of longer peripheral catheters (Chinnock et al, 2007; Elia et al, 2012; Liu et al, 2014; Stolz et al, 2015). For all patients considered DIVAs, those with one or more failed attempts, inability to identify veins visually or with a history of difficult access, use of ultrasound or other visual technologies is recommended to help obtain the preferred peripheral intravenous access (Gorski et al, 2016). Ultrasoundguided peripheral access (USGPIV), commonly inserted in the veins of the forearm, antecubital fossa or upper arm, is indicated for treatment duration less than 6 days or up to 15 days with a transition to midline catheter or PICC if treatment continues. USGPIV is also recommended for contrast-based radiographic studies requiring upper-extremity veins with larger catheters, 20-16 gauge, where visible veins to accommodate the size are not available (Table 2). Evidence supports greater success with ultrasound-guided peripheral catheter access after training (Schoenfeld et al, 2011). Greater success with these procedures results in reduced need and avoidance of CVADs (Gregg et al, 2010; Au et al, 2012; Shokoohi et al, 2013). Current research and guidelines support maintaining peripheral catheters until no longer clinically indicated or until a complication develops (Rickard et al, 2012; Gorski et al, 2012; Loveday et al, 2014; Tuffaha et al, 2014; Wallis et al, 2014; Bolton, 2015). Insertion of peripheral catheters into external jugular or leg veins is considered appropriate in emergent situations with verified inserter training prior to the insertion and treatment is 4 days or less (Chopra et al, 2015a). Peripheral catheters in the hand or distal portion of the upper extremity are the preferred choice when chronic kidney disease (CKD) is present and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is less than 44 ml/minute, stage 3b or greater, with a focus on preserving peripheral and central veins for haemodialysis, fistula or grafts (Chopra et al, 2015a). Peripheral catheters are the preferred access for all patients where no indication is present for central venous access (Chopra et al, 2015a). Increasing clinical skill with vein selection and access through the use of ultrasound and other visual aids facilitates the goal of avoiding CVADs when no indication exists for these devices. Many hospitals have incorporated vascular access teams to insert and maintain both peripheral and central catheters with positive outcomes (Hawes, 2007). The added expertise and skill of these team members supports the longer use of peripheral catheters.

Midline catheters

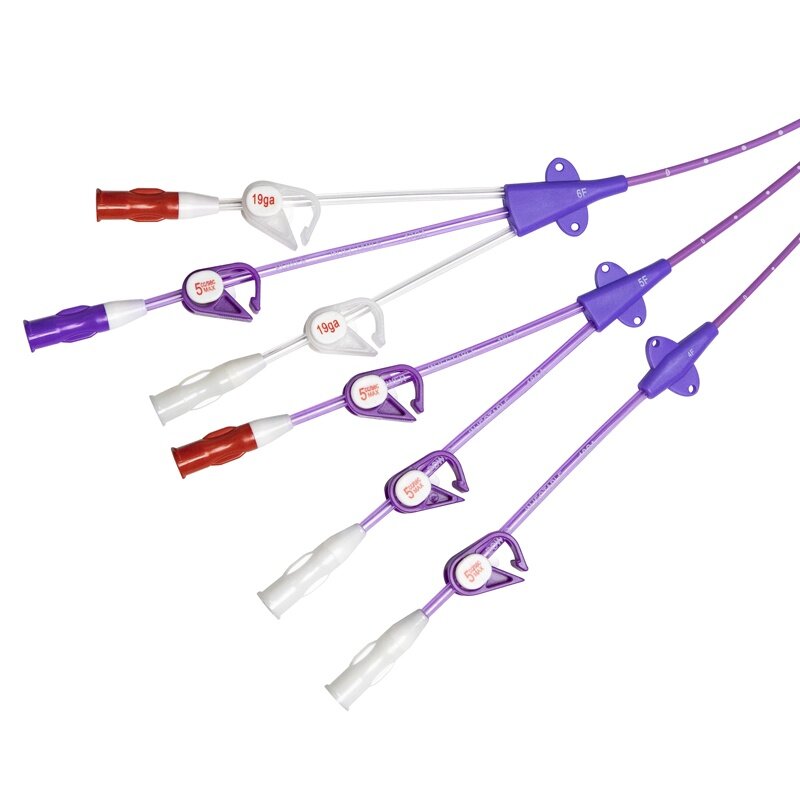

Midline catheters are experiencing a resurgence of attention with great usage owing to improvements in catheter materials and products. The two most recent midline catheters are 8–10 cm in length utilising the insertion technique referred to as accelerated Seldinger (AST) (Access Scientific, Bard Access Systems, Teleflex). These all-in-one devices with the modified Seldinger technique (MST) have the needle, wire and introducer in a combined unit for ease and speed in access. The evidence supporting midlines is growing with a variety of publications demonstrating positive outcomes (Anderson et al, 2004; Griffiths, 2007;Alexandrou et al, 2011; Cummings et al, 2011; Warrington et al, 2012; Dawson and Moureau, 2013; Caparas and Hu, 2014; Moureau et al, 2015). Midline catheters have lower phlebitis rates than peripheral catheters and lower rates of infection than other central catheters. Midlines are considered appropriate for patients with peripherally compatible solutions or medications where treatment will likely exceed 6 days. Midlines are preferred for patients requiring infusions up to 14 days, but may be used in a manner consistent with the clinically indicated removal of peripheral catheters (O’Grady et al, 2011; Caparas and Hu, 2014) (Table 3). When patients are considered DIVAs and ultrasound-guided peripheral access has failed, midlines are preferred (Figure 2). As with all vascular access devices, single lumen midline catheters are placed unless a specific indication for dual lumen is needed (only single and dual-lumen midlines are currently available).

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC)

PICCs have provided a reliable bridge between shorter peripheral catheters and chest-inserted central venous catheters (CICC) for more than 20 years (Figure 3). There is reduced risk of pneumothorax, haemothorax, nerve damage, stenosis and other more serious CVAD-related complications with PICC placement. Indications for PICCs (Table 4) include any patient requiring peripherally incompatible infusions or for intravenous treatment more than 14 days (Chopra et al, 2015a). Expanded nursing roles support safe placement of PICCs by specially trained teams of nurses (Robinson et al, 2005; Falkowski, 2006; Simcock, 2008). Increased awareness of PICCs has reduced the number of other CVAD placements. Bedside nurses are more likely to request a PICC order after having difficulty establishing peripheral access rather than considering all options and appropriateness of central access (Chopra et al, 2015b; Helm et al, 2015; Woller et al, 2015). With rising concerns over the incidence of thrombosis with PICCs and the relationship of thrombosis to infection, closer evaluation of each PICC request is necessary to evaluate the need for central versus peripheral access for each patient (Marschall et al, 2014; Chopra et al, 2015a). Measuring the vein diameter and choosing a catheter–to–vein ratio of 45% or less may reduce thrombosis risk in PICCs and midlines (Nifong and McDevitt, 2011; Sharp et al, 2015; Gorski et al, 2016). Use of antimicrobial PICCs may reduce risk and was statistically significant in reducing the level of infection by a factor of 4 in one hospital study (Rutkoff, 2014). In Tables 4 and 5 a list of appropriate and inappropriate indications for PICCs is provided based on MAGIC (Chopra et al, 2015a).

Non-tunnelled central venous catheters

Non-tunnelled CVCs are commonly used for internal jugular access with acute care patients who are unstable and who require haemodynamic monitoring or large fluid infusions. These percutaneously inserted catheters have a rate of infection similar to PICCs (Maki et al, 2006) and are used for short-term critical access. Non-tunnelled CVCs are preferred over PICCs when treatment is required for 14 days or less. Antimicrobial non-tunnelled catheters are often used for these critical patients when the catheter is expected to stay in place for more than 5 days to reduce risk of infection (Hockenhull et al, 2008; Pittiruti et al, 2009; Lai et al, 2013; Chopra et al, 2015a; Lorente et al, 2016) (Table 6).

Tunnelled central venous catheters

Tunnelled CVCs are inserted into internal jugular or subclavian veins with a subcutaneous tunnel commonly to the midchest region, but also other areas customised to the patient. Tunnelled catheters are indicated for use with intravenous treatment of 31 days or longer, or more episodic treatment over several months. Typically, these CVADs are reserved for patients not considered candidates for a PICC due to vein size or thrombosis risk. Tunnelled internal jugular catheters and small bore catheters are preferred for patients with any level of CKD requiring intravenous treatment for more than 15 days. PICC and tunnelled catheters are appropriate at all time intervals for infusion of irritating or chemotherapeutic medications. Tunnelled catheters are recommended over multilumen PICCs when multiple or frequent infusions are required due to their lower incidence of complications (Tran et al, 2010; Chopra et al, 2015a) (Table 7).

Subcutaneously implanted ports

With subcutaneously implanted ports, a catheter is inserted into either the internal jugular or subclavian vein and attached to a port reservoir. The port is implanted into a pocket created in a subcutaneous area on the chest (or arm as in arm ports), connected to the catheter, tested for flow and secured with sutures or glue (Simonova et al, 2012; Chopra et al, 2015a). Ports are appropriate for patients with expected treatment longer than 6 months. The MAGIC panelists rated ports as having neutral appropriateness for duration of treatment equal to 3-6 months. Ports may also be considered appropriate for difficult venous access if use for 31 days or more is expected (Chopra et al, 2015a)(Table 8).

Discussion

For the first time, the MAGIC document provides appropriateness ratings for specific VADs based on infusate, patient, duration and treatment characteristics. Factors such as proposed duration of medication infusions, effects of the medication on vessels, patient condition (renal, critical, chronic) or complications of infection were all evaluated (Figure 4), helping create clinically practical recommendations. However, recommendations for clinical appropriateness are often based on criteria that are difficult to estimate, such as duration of treatment. As emphasised by the patient panelist in the MAGIC initiative, an individualised approach is necessary in many situations. Application of the appropriateness criteria may also require adaptation to the particular care setting (hospital, skilled nursing, home environment). Factors such as reliability of the VAD are more important in the skilled nursing and home environment where clinical support and expertise may be limited. Peripheral catheters and midlines have variable reliability outside the hospital setting. The concept of vessel health and preservation is focused not just on gaining better outcomes during a single hospitalisation, but on preserving veins for future patient needs (Moureau et al, 2012; Hallam et al, 2016). Understanding and applying clinical research indicating the treatment, practice or process leading to the best results for the patient is challenging for clinicians. Selection of recommendations and guidelines is often convenience and economically oriented rather than patient focused, leading to a greater risk of complications for the patient. It is important to remember that limitations exist for the MAGIC guidance. First, not all recommendations translate to all patient populations. For instance, placement of CVCs in critically ill patients requires the availability of experienced and skilled staff to insert devices in manners that are safe from insertion complications such as pneumothorax. This is implicitly assumed in MAGIC, but may not be so in the real world. Second, MAGIC does not address certain technological advances including antimicrobial-coated catheters or advanced devices such as infra-red vein finders that may impact on choice and selection of device. These limitations must be borne in mind when considering MAGIC. Technology ever advances and MAGIC should thus not be viewed as an all-encompassing document, but a living and breathing statement that changes with available evidence and practice. Third, it is unclear how best to implement recommendations from MAGIC. Should these be incorporated into checklists, software-based applications or electronic-medical record systems? Who is responsible for adherence? Are there potential barriers in implementation that have not been considered? These types of challenges require careful thought and the use of implementation science to better understand what works and what does not in the real�world setting. MAGIC has succeeded in creating a practical list of indications, both appropriate and inappropriate, for VAD use. This document guides physicians, bedside clinicians, and those on vascular access teams to the most appropriate selection of the safest device and practices for the patient. To quote Thomas Vesely, a fellow clinician and designated Doctor of Medicine, who spoke to the authors:

‘More than 20 nationally-recognised guidelines, recommendations, and standards documents concerning vascular access were created by 10 different organisations. Insular creation of such documents is the wrong approach. It’s time that all involved agree on ‘the rules’ even if that requires compromise and MAGIC is a good step in the right direction.’

More expert discussion, evaluation and research is needed on issues where panelists failed to reach a decision, were neutral or disagreed for VAD indications. Consistent with the variation in panelist responses, published literature often has contradictions in results from one study to another. There was a paucity of randomised controlled trials for specific VADs necessary to establish definitive conclusions. Furthermore, what works in one setting may not work in another. Understanding how best to implement MAGIC to improve decision-making in vascular access remains a key goal—one that must be actively targeted by those in this field. Conclusion Guidelines, recommendations and standards point to the need for evidence-based indications when selecting a VAD. Relying on available literature, the combined clinical experience of the panelists, patient input, and an established methodology embodied in the RAND/UCLA Method, a consensus was reached through MAGIC to establish a working guide for intravenous device indications and contraindications. Careful evaluation and application of MAGIC conclusions into the programme of each facility administering intravenous treatments provides guidance toward the most appropriate and safe patient applications. In this age of electronic medical records, criteria such as MAGIC may serve as a clinical decision process embedded in the electronic medical records framework to guide clinical decisions in keeping with the theory of vessel health and preservation for patients from birth to death.