Catheter Nursing Professional Committee of Qingdao Nursing Association

Venous Thromboembolism Professional Committee of Qingdao Nursing Association

Pain Management Professional Committee of Shandong Nursing Association

【Abstract】 Objective To develop the Expert Consensus on Peripheral Arterial Catheter Management in Adult ICU Patients (hereinafter referred to as the Consensus). Methods Based on a problem-oriented approach and a review of relevant domestic and international literature, the Consensus was formulated through Delphi expert consultation and expert argumentation meetings. Results The Consensus comprises five sections: pre-catheterization evaluation, catheter indwelling, observation and maintenance during catheterization, preventive measures for complications, and catheter removal, with a total of 33 recommended items. Conclusions The Consensus is scientifically sound and highly applicable in clinical practice, providing guidance and reference for the clinical management of peripheral arterial catheters in adult ICU patients.

【Key words】 Intensive Care Units; Adult; Peripheral arterial catheter; Expert consensus

DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115682-20230529-02126

Peripheral arterial catheters are percutaneously inserted into arteries and remain in the lumen to communicate with the external environment. They are used for blood pressure monitoring, assessment of blood volume, and arterial blood sampling, serving as a primary tool for hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients. They reduce the pain and vascular injury caused by repeated punctures [1]. Critically ill patients often have poor vascular conditions, making catheterization difficult, and prolonged indwelling increases the risk of adverse events due to improper management, such as catheter-related bloodstream infections [2-3], bacterial colonization [4], accidental extubation [5], bleeding or exudation at the puncture site [6], catheter occlusion [7], local swelling, pain, and even limb ischemia or necrosis [8], which affect clinical outcomes. Existing domestic and international guidelines mention peripheral arterial catheter management [9-10] but lack specificity and targeting. Additionally, studies show that ICU nurses' overall awareness of evidence-based knowledge related to catheter management is only 62.38%, with merely 3.38% able to perform nursing operations based on such evidence [11]. Despite the high usage rate of peripheral arterial catheters in ICU patients, there is a lack of targeted and authoritative management standards. Therefore, our research team invited domestic medical and nursing experts in related fields to form an expert group and compile this Consensus to standardize management procedures and guide clinical practice.

I. Formulation of the Consensus

1.Establishment of the Consensus writing group: The group was led by the Pain Management Professional Committee of Shandong Nursing Association, Catheter Nursing Professional Committee of Qingdao Nursing Association, and Venous Thromboembolism Professional Committee of Qingdao Nursing Association. It included 4 chief nurses, 2 senior nurses, and 1 full-time nursing master’s student. Chief nurses were responsible for formulating the research topic, quality control, and organizing writing meetings; senior nurses handled expert liaison, distribution of consultation questionnaires, literature quality evaluation, evidence summarization, and revision of the Consensus; the master’s student was in charge of literature retrieval and data analysis. All members received training in evidence-based nursing.

2.Proposal of research questions: Clinical nursing experts identified the research question of "improving the compliance rate of standardized management of peripheral arterial catheters in critically ill patients" based on the current management status. A problem-oriented approach was adopted to review domestic and international literature and form the framework of the Consensus.

3.Literature retrieval and quality evaluation: Retrieval resources included guideline websites (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network, Guideline International Network), evidence-based databases (Cochrane Library, Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Evidence-Based Healthcare Center, UpToDate), and Chinese and English primary databases (Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, CNKI, CBM, Wanfang Data). Chinese search terms included "invasive arterial pressure monitoring/invasive blood pressure/radial artery puncture/radial artery catheterization/peripheral arterial catheter/blood gas analysis", "peripheral arterial catheter-related complications/catheter-related bloodstream infection/puncture site bleeding/puncture site ecchymosis/local hematoma/limb ischemia/catheter dysfunction", and "clinical decision/guideline/evidence summary/systematic review/expert consensus". English search terms included "arterial catheters/lines/vascular access/invasive blood pressure/peripheral arterial catheters/catheterization/radial artery catheterization", "intravascular catheter-related infection/catheter-related bloodstream infection/CRBSI/CLABSI/arterial catheter-related bloodstream infection", and "clinical decisions/guidelines/evidence summaries/systematic reviews/consensus". After systematic retrieval and screening, two team members independently evaluated literature quality: systematic reviews and expert consensuses were assessed using the JBI Evaluation Criteria (2016) [12], and guidelines using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation Ⅱ (AGREE Ⅱ) [13]. Disagreements were resolved by a third researcher through re-evaluation and discussion. A total of 12 high-quality literatures were included, consisting of 1 guideline, 3 evidence summaries, 3 systematic reviews, and 5 expert consensuses.

4.Selection of consulting experts: Experts from 10 provinces, including Shandong, Sichuan, and Hubei, were invited. Inclusion criteria: (1) engaged in critical care medicine, critical care nursing, or management; (2) ≥10 years of work experience in related fields; (3) associate senior title or above; (4) master’s degree or above.

5.Development of expert consultation questionnaires: Questionnaires included an introduction to the research purpose, expert basic information, and the content of the Consensus. Expert basic information covered general data, basis for expert judgments, and familiarity with the survey content.

6.Consultation methods and expert argumentation meetings: Questionnaires were sent to experts after obtaining their consent, requiring evaluation of the necessity, feasibility, practicality, and clinical significance of the Consensus recommendations, with feedback and revisions within one week. Two rounds of consultation were conducted with experts from the same pool, separated by 2 weeks. In the second round, experts with low familiarity were excluded. After the first round, the questionnaire was revised to form the second-round version, which was further adjusted based on expert opinions. Post-consultation, an argumentation meeting was held. Recommendations were classified into Levels 1-5 using the JBI Evidence Pre-grading and Recommendation System (2014 edition) [14], and recommendation strength (strong or weak) was determined based on expert analysis of the pros and cons of each item. Recommendations with inconsistent opinions had their strength downgraded to finalize the Consensus.

7.Statistical methods: Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0. Normally distributed measurement data were described as mean ± standard deviation (\bar{x} \pm s), and count data as frequencies and percentages (%). Expert authority was represented by the authority coefficient (Cr), calculated as the arithmetic mean of the judgment basis coefficient (Ca) and familiarity coefficient (Cs). Expert enthusiasm was reflected by the effective recovery rate of questionnaires. Expert opinion consistency was evaluated using the coefficient of variation and Kendall's harmony coefficient. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

II. Results

1.General characteristics of consulting experts: A total of 21 experts participated in the two rounds of consultation, with an average age of (45.32 ± 11.35) years (range: 42-54 years). Among them, 3 held doctoral degrees and 18 held master’s degrees, with an average work experience of (19.49 ± 4.47) years (range: 12-27 years).

2.Consultation results: (1) Expert enthusiasm, authority, and opinion consistency: The first round distributed 23 questionnaires, with 21 valid responses (effective recovery rate: 91.30%). The second round distributed 21 questionnaires, with 21 valid responses (effective recovery rate: 100.00%). The Ca was 0.786, Cs was 0.897, and Cr was 0.842, indicating high expert authority and reliable results. Kendall's harmony coefficients for overall recommendations in the two rounds were 0.354 and 0.467 (P < 0.05). The coefficients of variation for overall recommendations were < 20.00% in the first round and < 15.00% in the second round, indicating high consistency. (2) Expert revisions: In the first round, 17 experts proposed 15 revisions: ① Additions: "catheter removal", "selection of appropriate catheters (length, material, diameter) based on vascular conditions and improvement of puncture skills to avoid repeated punctures", "inquiry of awake patients about pain, swelling, or numbness in the punctured limb after catheterization", and "removal indications". ② Revisions: "observation and management of complications" was changed to "preventive measures for complications"; the secondary topic "catheterization site" was moved under the primary topic "catheter indwelling"; "use of local anesthetics to reduce pain and vasospasm" was revised to "local anesthesia with lidocaine is recommended for awake patients not receiving analgesia or sedation"; "intra-arterial injection of heparin, nitroglycerin, sodium nitroprusside, verapamil, phentolamine, and systemic sedatives" was revised to "physical methods for preventing and relieving spasm, such as local massage and warmth". ③ Deletions: "evaluation of hand blood flow using arterial angiography or magnetic resonance angiography", "during treatment for bleeding tendency or hypercoagulable state", "vasculitis and Raynaud's syndrome", "guidewire-guided puncture", "content related to waveform influence", "routine use of antimicrobial dressings", "use of closed blood collection systems or intra-arterial blood gas monitoring", "chlorhexidine cleaning of the puncture site before removal", and "blood aspiration before removal". In the second round, experts reached high consistency with no further revisions.

III. Content and Interpretation of the Consensus

(I) Pre-catheterization Evaluation

1.Indications: Peripheral arterial catheters are widely used in critically ill patients, including those with hemodynamic instability, inability to undergo non-invasive blood pressure measurement, need for evaluating volume responsiveness or assisting diagnosis via hemodynamic waveform changes (2a, A); difficulty in blood sampling or need for repeated arterial blood sampling (2a, A); and patients undergoing major surgeries with risks of massive bleeding, requiring controlled hypotension, hypothermic anesthesia, or cardiac output monitoring [15-16] (2a, A).

2.Contraindications: There are no absolute contraindications, but relative contraindications include ipsilateral radial artery in patients with positive modified Allen’s test (5b, A); local vascular anatomical abnormalities, existing or potential infection, trauma, or planned surgery at the puncture site [16] (4a, A).

(II) Catheter Indwelling

1.Personnel qualifications: Studies show that anesthesiologists are the primary operators for peripheral arterial catheterization [17]. In tertiary hospitals, 45.2% of ICU nurses and 41.1% of physicians participate in catheterization, with 31.9% of ICU nurses routinely performing arterial catheterization [18]. Proficiency in catheterization is closely related to complications. Thus, clinical departments using peripheral arterial catheters should develop standardized operation protocols, and both medical and nursing staff should receive relevant training [19-20]. The Consensus recommends that ICU medical staff performing catheterization be certified and professionally trained [21-23] (3b, B).

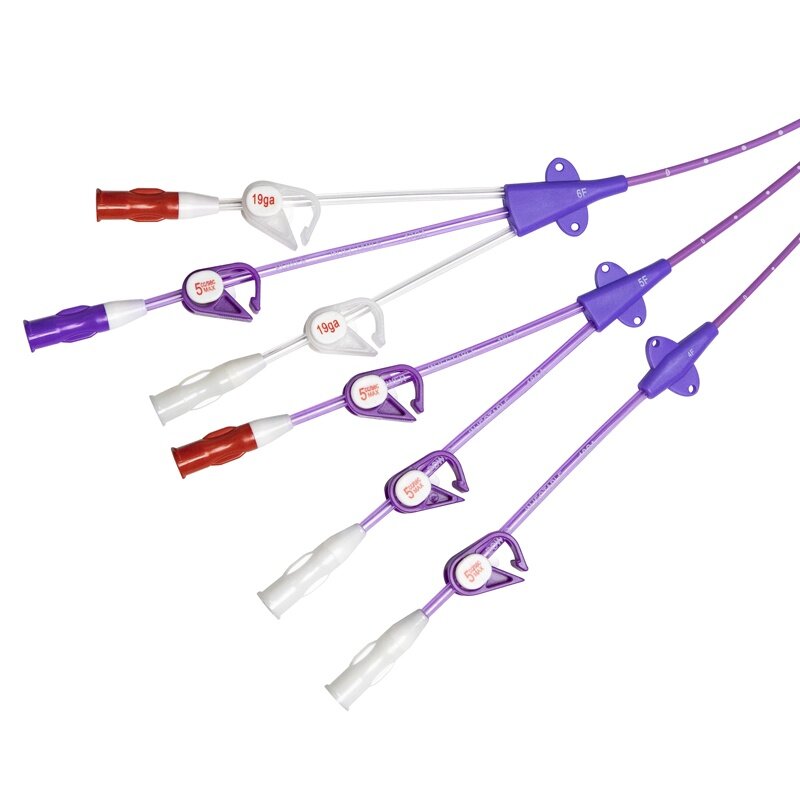

2.Catheterization site: (1) Puncture site: The radial artery is the most common site, preferably the left radial artery, followed by the brachial, ulnar, and dorsalis pedis arteries [15, 21-22] (5b, A). The radial artery lies in the longitudinal groove between the flexor carpi radialis tendon and the distal radius, with palpable pulsations above and below the radial styloid process, making it the optimal site. (2) Evaluation: Routine Allen’s test is performed before catheterization to assess adequate collateral flow from the ulnar artery’s superficial palmar arch after radial artery occlusion. Hand blood flow can be evaluated by palpation, Doppler ultrasound, or pulse oximetry [16, 21-24] (3b, B). Methods for assessing radial artery palmar collateral circulation include the classic Allen’s test, modified Allen’s test, and pulse oximetry-assisted Allen’s test [25]. The latter avoids subjective judgment, being non-invasive, easy to operate, and cost-effective. Doppler ultrasound, using out-of-plane (short-axis) and in-plane (long-axis) techniques, improves first-attempt success and reduces puncture attempts [26]. (3) Puncture procedure: ① Peripheral arterial catheterization follows standard aseptic principles, with all components of the pressure monitoring system (calibration equipment and flushing solution) maintained sterile [21, 23] (5a, A). ② The non-dominant hand palpates the artery, and the dominant hand performs the puncture. Ultrasound guidance is recommended for difficult direct punctures [22, 27] (4b, B). ③ Pre-flush the system and adjust the monitoring equipment in advance. After catheter insertion and needle withdrawal, compress the artery proximally to prevent bleeding during connection to the monitoring line [15, 27] (4b, B). (4) Documentation: Arterial catheters should be clearly labeled, securely fixed, with records of catheterization site, date, dressing change time, and removal date [21-22, 28] (5b, A). Special labels distinguish them from nutritional or intravenous therapy accesses.

(III) Observation and Maintenance During Catheterization

Observation and maintenance include monitoring blood pressure values and waveforms, standardizing pressure sensor use, maintaining flushing and monitoring systems, and local dressing changes.

1.Observation of blood pressure values and waveforms: (1) Effects of site and position: Transducers convert physiological pressure signals into electrical signals for continuous, accurate blood pressure measurement, which varies with catheter position [29-30]. Compared to the radial artery, the dorsalis pedis artery may have a 10 mmHg higher systolic pressure and 10 mmHg lower diastolic pressure [15, 24] (4b, A). Systolic pressure in the left lateral position is lower than in the supine and right lateral positions, and invasive arterial pressure increases with rising head-of-bed angle [15, 20] (4d, A). (2) Waveform monitoring: Waveform analysis helps assess volume responsiveness, and respiratory waveform variability can evaluate fluid challenge efficacy [15] (5c, A). A stable arterial waveform is fundamental for accurate blood pressure and hemodynamic measurement, determined by the system’s natural frequency (pressure pulse oscillation frequency) and damping coefficient (oscillation attenuation). Excessive stiffness or transducer defects cause under-damping, manifesting as high systolic pressure, low diastolic pressure, and wide pulse pressure. Low flushing bag pressure, air bubbles, thrombi, or connection failure cause over-damping, with low systolic pressure, high diastolic pressure, and narrow pulse pressure. Medical staff should maintain stable waveforms to ensure accurate readings [31].

2.Standards for pressure sensor use: (1) Position: The sensor should be at the heart level (intersection of the 4th intercostal space and midaxillary line); deviations cause pressure errors [15-16, 22] (5a, A). (2) Zero calibration: Calibrate when first used or after position changes, and every 4-6 hours during continuous use [32]. (3) Replacement frequency: Disposable sensors are recommended, replaced every 96 hours or immediately if contaminated [21] (2b, A). The sensor should align with the venous hydrostatic axis during monitoring; a high position underestimates pressure, and a low position overestimates it, though the fluctuation range remains controversial [33-35].

3.Flushing system: (1) Pressure and rate: Closed, continuous flushing systems maintain catheter patency with 300 mmHg pressure and 3 ml/h flow. Manual flushing should be gentle, avoiding prolonged high-pressure flushing via the system valve [15-16, 21-22, 36] (1b, A). (2) Flushing solution: 0.9% sodium chloride is preferred; heparinized flushing solution requires evaluation of contraindications [21-22] (2b, A). Flushing methods include intermittent syringe injection, continuous infusion via infusion pumps, or pressurized infusers. Open systems increase infection and arterial thrombosis risks. Immediate flushing is required after blood sampling or detection of backflow to prevent thrombus formation [20].

4.Monitoring system: Avoid air entry into the line or blood [16] (4b, A). Residual air may cause embolism or inaccurate measurements; air in blood weakens mechanical signals or causes erroneous readings.

5.Dressing changes: (1) Aseptic technique: Strict aseptic principles are followed [18, 20] (5a, A). (2) Dressing selection: Sterile transparent semipermeable dressings are routine, replaced every 7 days or immediately if moist, loose, contaminated, or if puncture site bleeding/exudation occurs [18, 28] (4a, A). Studies show 91.5% of ICU nurses use transparent dressings, while only 5.9% use antimicrobial dressings [37]. The Guidelines for Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections (2014) note that chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings reduce bloodstream infections and bacterial colonization [10], but their routine use remains controversial.

(IV) Preventive Measures for Complications

Unplanned extubation (UEX) is the most serious mechanical complication, with an incidence of 25%-42%. Risk factors include age > 65 years, hypertension, venous thromboembolism, radial artery catheterization, and use of intravenous catheters [38]. As an invasive procedure, peripheral arterial catheterization damages tissues; timely removal is most effective in reducing complications. The Consensus recommends daily evaluation of catheter necessity and early removal [21-23] (5a, A). Catheter-related bloodstream infection, the most severe complication, has an incidence of ~3.3/1000. Critically ill patients’ immunosuppression and intensive ICU interventions increase infection risk, with a 25% higher mortality if infected [39-40]. The Consensus recommends that emergently placed catheters with suboptimal asepsis be removed within ≤ 48 hours [21-22] (3e, A). Coagulopathy and anticoagulant use increase puncture site bleeding risk, which is also related to catheter material, indwelling time, and catheterization setting [41]. The Consensus recommends selecting appropriate catheters based on vascular conditions and improving puncture skills [21-23] (3b, A). Routine catheter replacement is unnecessary during indwelling, with a usual maximum duration of ≤ 7 days [21-22] (2b, A). Regular observation and assessment during indwelling are critical for prevention: daily checks of local pulse, skin color, and temperature [15, 24] (2c, A); inquiry of awake patients about pain, swelling, or numbness in the punctured limb [24] (4a, B).

(V) Catheter Removal

1.Timing: Remove immediately if there are signs of infection, catheter dysfunction (waveform abnormalities, no backflow, displacement), unexplained fever, or if the catheter is no longer needed [15, 21-22] (5c, A).

2.Pre-removal evaluation: Check coagulation indices (INR, APTT, platelet count) and inspect catheter integrity after removal [15, 21-22] (5c, A).

3.Post-removal compression: Compress radial artery puncture sites for 5 minutes; extend to 10 minutes for patients with coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia. If bleeding persists, recheck after an additional 5 minutes of compression before dressing [15, 20] (2b, B).

4.Post-removal observation: Reassess the puncture site and distal pulse 15 minutes after removal to check for hematoma or limb ischemia [15] (4a, A). Peripheral arterial catheters provide reliable data for patient assessment, serving as the gold standard for hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients [42].

Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Consensus Committee Members

Writers: Jiang Yan (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Gao Silong (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Wei Lili (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Gai Yubiao (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University)

Secretarial Team: Song Qingna (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Guo Xiaojing (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Zhang Yaoyao (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University)

Consulting Experts: Li Zunzhu (Peking Union Medical College Hospital), Tian Yongming (West China Hospital of Sichuan University), Sun Shichang (Xiangya Hospital of Central South University), Dong Jianbin (The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University), Zhu Shichao (Henan Provincial People’s Hospital), Yan Pengbo (Tianjin Beichen Hospital), Xu Liqun (Air Force Medical University, Harbin), Yin Yanling (The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University), Zhang Zhigang (The First Hospital of Lanzhou University), Wu Wenjing (Shanxi Bethune Hospital), Ding Min (Shandong Provincial Hospital), Wang Jing (Qilu Hospital of Shandong University), Jiang Shumin (Shandong Qianfoshan Hospital), Sun Shuqing (Weifang People’s Hospital), Sun Yunbo (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Xing Jinyan (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Jiang Wenbin (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Su Yuan (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Shan Liang (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Cheng Huawei (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University), Lin Hui (The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University)

References

[1] Hua T. Risk factors and prediction model construction for failed radial artery puncture and catheterization in patients [D]. Shanghai: Naval Medical University, 2018.

[2] O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2011, 52(9): e162-e193. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cir257.

[3] López-López C, Collados-Gómez L, García-Manzanares ME, et al. Prospective cohort study on the management and complications of peripheral venous catheter in patients hospitalised in internal medicine[J]. Rev Clin Esp (Barc), 2021, 221(3): 151-156. DOI: 10.1016/j.rceng.2020.05.014.

[4] Levinson AT, Chapin KC, LeBlanc L, et al. Peripheral arterial catheter colonization in cardiac surgical patients[J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2018, 39(8): 1008-1009. DOI: 10.1017/ice.2018.127.

[5] Zhang YQ, Zou DX, Deng J, et al. Application of modified radial artery catheterization in ICU patients[J]. Chin J Emerg Crit Care Nurs, 2022, 3(4): 341-344. DOI: 10.3761/j.issn.2096-7446.2022.04.010.

[6] Kale SB, Ramalingam S. Spontaneous arterial catheter fracture and embolisation: unpredicted complication[J]. Indian J Anaesth, 2017, 61(6): 505-507. DOI: 10.4103/ija.IJA-181-17.

[7] Lee MO, Jeong KU, Kim KM, et al. Risk factors affecting complications of access site in vascular intervention through common femoral artery[J]. Niger J Clin Pract, 2022, 25(1): 85-89. DOI: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_37_21.

[8] Schults JA, Long D, Pearson K, et al. Insertion, management, and complications associated with arterial catheters in paediatric intensive care: a clinical audit[J]. Aust Crit Care, 2020, 33(4): 326-332. DOI: 10.1016/j.aucc.2019.05.003.

[9] Medical Administration Bureau, National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Guidelines for Prevention and Control of Vascular Catheter-Related Infections (2021 Edition)[EB/OL]. (2020-03-30)[2024-03-01]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7659/202103/dad04cf7992e472d9de1fe6847797e49.

[10] Loveday HP, Wilson JA, Pratt RJ, et al. Epic 3: national evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2014, 86 Suppl 1: S1-S70. DOI: 10.1016/S0195-6701(13)60012-2.

[11] Li JF, Han Y, Shen F, et al. A survey on evidence-based knowledge and practice of peripheral arterial catheters among ICU nurses[J]. J Nurs Train, 2022, 37(7): 663-667. DOI: 10.16821/j.cnki.hsjx.2022.07.019.

[12] Hu Y, Hao YF. Evidence-Based Nursing[M]. 2nd ed. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2018: 52-80.

[13] Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care[J]. CMAJ, 2010, 182(18): E839-E842. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.090449.

[14] Wang CQ, Hu Y. JBI Evidence Pre-grading and Recommendation Level System (2014 Edition)[J]. J Nurs Train, 2015, 30(11): 964-967.

[15] Arthur CT, Gilles C, Michael FO, et al. Indications, interpretation, and techniques for arterial catheterization for invasive monitoring[EB/OL]. (2022-11-02)[2024-03-04]. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/zh-Hans/intra-arterialcatheterization-for-invasive-monitoring-indications-insertiontechniques-and-interpretation?search=Indications%2C%20interpretation%2C%20and%20techniques%20for%20arterial%20catheterization%20for%20invasive%20monitoring&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.

[16] Ma H, Wang J, Ye JR, et al. Expert consensus on radial artery puncture, catheterization and pressure monitoring[EB/OL]. (2018-09-28)[2024-03-04]. https://wenku.baidu.com/tfview/21d9cc92504de518964bcf84b9d528ea81c72f25.html?fr=launch_ad&utm_source=360ss-WD&utm_medium=cpc&utm_account=SS-360tg01&qhclickid=f38406bfa21211bd.

[17] Yuan C, Yang XY, Xiao YY, et al. Incidence of complications during peripheral arterial catheterization and influencing factors of puncture-site bleeding in ICU patients[J]. Chin Nurs Manag, 2022, 22(11): 1612-1617. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2022.11.003.

[18] Tang WH, Chen Y, Zhu YP, et al. Mastery status of invasive blood pressure monitoring skill of intensive care unit nurses and improvement countermeasures[J]. Nurs Prac Res, 2016, 13(13): 81-83. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-9676.2016.13.035.

[19] Wei L, Li Y, Li XY, et al. Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for the prophylaxis of central venous catheter-related complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2019, 19(1): 429. DOI: 10.1186/s12879-019-4029-9.

[20] Sun H, Li CY. Clinical Practice Standards for Adult Arterial Blood Gas Analysis (2nd Edition). (2022-08-05)[2024-03-01]. https://www.bjhlxh.com/website/detail/%E9%A6%96%E9%A1%B5/%E8%A1%8C%E4%B8%9A%E8%B5%84%E8%AE%AF/7650b646a0564430b618843398d05bfe/902daa5372f1422297a51f2f24fff9ef/%2Fwebsite%2Flist.

[21] Li JF, Shen F, Li ZSZ, et al. Evidence-based practice of peripheral arterial catheter maintenance in ICU adult patients[J]. Chinese Nursing Research, 2022, 36(17): 3121-3126. DOI: 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2022.17.019.

[22] Wang Y, Han L, Yuan C, et al. Best evidence summary for peripheral arterial catheterization insertion and maintenance in adult ICU patients[J]. Chin J Nurs, 2020, 55(4): 600-606. DOI: 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2020.04.023.

[23] Guo HH, Chen MG, Kong LL, et al. Evidence-based practice of best replacement of catheter for arterial pressure measuring of critically-ill patients[J]. J Nurs, 2021, 28(2): 37-41. DOI: 10.16460/j.issn1008-9969.2021.02.037.

[24] Ying Y, Lin XJ, Chen MJ, et al. Evidence in cardiovascular anesthesia (EICA) group. Severe ischemia after radial artery catheterization: a literature review of published cases[J]. J Vasc Access, 2022, 11297298221101784. DOI: 10.1177/11297298221101784.

[25] Zhen YJ, Hou Q, Shi SS, et al. Research on consistency between Allen's test under pulse oxygen monitoring and classical Allen's test[J]. Chinese Nursing Research, 2023, 37(9): 1636-1639. DOI: 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2023.09.023.

[26] Hofmann LJ, Reha JL, Hetz SP. Ultrasound-guided arterial line catheterization in the critically ill: technique and review[J]. J Vasc Access, 2010, 11(2): 106-111. DOI: 10.1177/112972981001100204.

[27] Joanna Briggs Institute. Arterial lines: insertion[EB/OL]. (2017-02-14)[2023-05-29]. http://connect.jbiconnectplus.org/Search.aspx.

[28] Joanna Briggs Institute. Arterial lines: dressing[EB/OL]. (2017-02-14)[2023-05-29]. http://connect.jbiconnectplus.org/Search.aspx.

[29] Liang XJ, Zhu HJ, Guo JY, et al. Research progress on related factors affecting the accuracy of invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring in critically ill patients[J]. Chinese Journal of Disaster Medicine, 2022, 10(2): 84-87. DOI: 10.13919/j.issn.2095-6274.2022.02.006.

[30] Qian FP, Chen QL, Wang JH, et al. Analysis and research on factors influencing the efficacy of invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring system[J]. Chin J Mod Nurs, 2014, 20(12): 1425-1427. DOI: 10.3760/j.issn.1674-2907.2014.12.024.

[31] Saugel B, Kouz K, Meidert AS, et al. How to measure blood pressure using an arterial catheter: a systematic 5-step approach[J]. Crit Care, 2020, 24(1): 172. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-020-02859-w.

[32] Zhou J, Zuo XR, Liu SH, et al. Discussion on the zero-calibration and the zero line in the measurement of central venous pressure and invasive arterial blood pressure[J]. Chin Crit Care Med, 2023, 35(3): 316-320. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121430-20220926-00862.

[33] Netea RT, Bijlstra PJ, Lenders JW, et al. Influence of the arm position on intra-arterial blood pressure measurement[J]. J Hum Hypertens, 1998, 12(3): 157-160. DOI: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000479.

[34] Liu PP, Dai MH, Li L, et al. Influence of pressure sensor position and arterial limb position on continuous invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring in children[J]. J Bengbu Med Coll, 2017, 42(12): 1716-1717. DOI: 10.13898/j.cnki.issn.1000-2200.2016.12.047.

[35] Peng HF. Influence of pressure sensor position and arterial limb position on continuous invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring[J]. China Med Device Inf, 2018, 24(20): 40-41. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-6586.2018.20.020.

[36] Joanna Briggs Institute. Arterial lines: placement[EB/OL]. (2017-02-14)[2023-05-29]. http://connect.jbiconnectplus.org/Search.aspx.

[37] Yang K. Investigation and research on ICU nurses' cognition status of peripheral catheter indwelling and maintenance[J]. International Medicine and Health Guidance News, 2022, 28(4): 568-571. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-1245.2022.04.031.

[38] Luan C, Guo F, Ji Y. Construction of risk prediction model for unplanned peripheral arterial catheter extubation in ICU patients and its verification[J]. J Nurs Sci, 2023, 38(6): 63-67. DOI: 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2023.06.063.

[39] O'Horo JC, Maki DG, Krupp AE, et al. Arterial catheters as a source of bloodstream infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Crit Care Med, 2014, 42(6): 1334-1339. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000166.

[40] Wang B, An YZ. The current understanding of arterial-catheter related bloodstream infection[J]. Chin Crit Care Med, 2016, 28(5): 478-480. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2016.05.021.

[41] Chao CB, Xu Y. Research progress on factors influencing indwelling time of arterial indwelling needles and nursing countermeasures[J]. J Xuzhou Med Univ, 2019, 39(3): 232-234. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.2096-3882.2019.03.018.

[42] Zhu HR. Development of an invasive blood pressure simulation system[D]. Chengdu: University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, 2021.

===========================================================

Received date: 2023-05-29

Editor: Sun Mengyuan

Citation: Catheter Nursing Professional Committee of Qingdao Nursing Association, Venous Thromboembolism Professional Committee of Qingdao Nursing Association, Pain Management Professional Committee of Shandong Nursing Association. Expert consensus on peripheral arterial catheter management in adult ICU patients[J]. Chin J Mod Nurs, 2024, 30(11): 1401-1406. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115682-20230529-02126.